When using a 3D graphics application, a lot of time is spent just placing and moving objects. Since this workflow is so critical, a lot of thought has gone into designing tools to facilitate it. Let’s explore them!

Basic

In a 2D application, you can just let the user click and drag the object where they want since this operation is pretty unambiguous. When the user drops the object, you know where they are dropping it in 2D space. In 3D space though, the cursor’s position can be translated to a line of infinite points. So on its own, click and drag can’t provide the basic move controls.

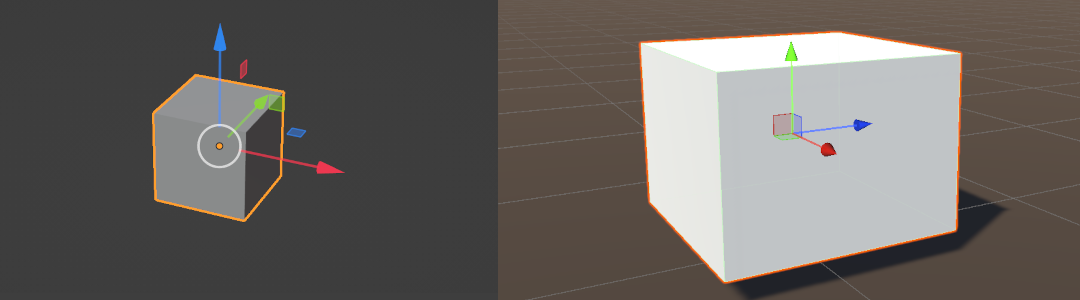

That’s why basically all 3D applications provide a “gizmo”, a UI overlay showing three axes, to move the object in 3D space. You drag the axis to move the object in that direction. Most gizmos will also have “planes” that you can drag to constrain the movement to two dimensions.

It is worth highlighting that Blender users use the keyboard shortcuts more often: g to enter “grab” mode, followed by additional keys to constrain the movement in one direction (x, y, z) or two directions (shift+x, shift+y, shift+z).

Snapping

Moving objects around by clicking on the arrows can let you control the direction but it’s hard to have a lot of precision. To provide that missing precision, 3D applications use snapping.

Let’s take two concrete examples and see how different snapping tools can help.

- I want to place a chair on the ground so it rests exactly on the ground. Not floating a few inches up or sinking a few inches into the ground.

- I have two walls that I want to connect together. There should be no gap in between.

Changing Pivot

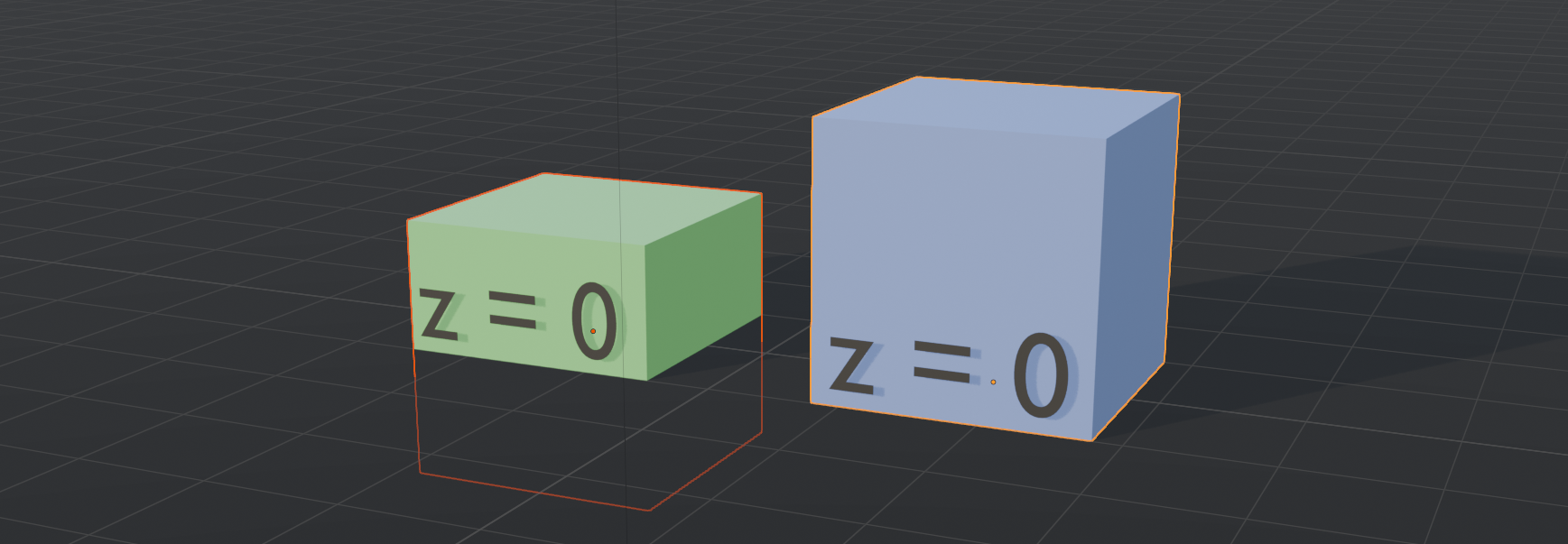

Before discussing solutions, let’s talk about pivot points. Every object has a

pivot point that we treat as the “center” of the object. When you set an object

to an exact position like (0, 0, 0), it is this point of the object that will

be placed there. The rest of the object is placed relative to this pivot point.

So any transformation happens with respect to the pivot points.

Artists will usually place pivots specifically to make placement workflows easier. For example, if an object is expected to be placed on the ground, then the pivot of the object will be at the bottom. If the object is expected to be connected to other objects, the pivot will be set at these connecting points.

Sometimes, though, an object can have many connecting points and you can only have one pivot. If you are caught in a situation where the pivot isn’t where you want, you usually have two options:

- Sometimes the application has special workflows to move the pivot temporarily.

Unreal is a good example here which allows you to move the pivot using

alt+v. This way you can set the pivot where it is useful right now, do your manipulations, and then reset the pivot. - Alternatively, a dummy “parent” can be used to emulate a custom pivot. This is done by creating an “empty” object and placing it where you want the pivot to be. Then make the original object a child of this empty object. After that, any manipulations of the empty object will “trickle” down to the child such that it will behave as a virtual pivot point.

These two solutions are useful because the snapping workflows are essentially snapping the position of the pivot. So being able to treat some other point as a pivot gives you more flexibility in the workflow.

Grid

2D applications snap objects using screen pixels. As you slowly move an object, the object will move 1 screen pixel at a time, giving you good control. If you need finer control you can zoom in to get more screen pixels for your canvas.

In 3D applications, you are moving objects in 3D space. A screen pixel translates to different distances at different points. Using different distances for snapping creates a more confusing experience. So instead, 3D applications rely on snapping in 3D world space.

How does the grid perform with our two use cases?

- The grid helps us place the ground precisely at 0 height. Then we can use the grid again to place the chair at exactly the same height. This will work great if the chair’s pivot point is at the bottom of the chair. If it doesn’t, though, then we need one of the tricks described in the pivot section.

- The grid is less helpful when we want to connect our walls. There is no reason that our walls are going to be exactly the size of the grid or be aligned with the grid. That means the corners of the walls are frequently going to be at non-grid points. So we need something else to help us align the two objects.

Geometry

Luckily, geometry snapping is there to help align objects. By geometry snapping, we mean taking the meshes (aka the geometry) and using that to figure where to place the objects.

A mesh can be seen through many lenses (vertices, edges, faces, normals, bounding box). If we are going to use the mesh to help align objects, what aspects of the mesh are we actually looking at? Well, there are two objects, the source and the target so let’s look at them individually:

- Source object: The object that we are moving is the source object. What point of the source should we use for snapping? The simple answer is to use the pivot. If the user wants to use a point of the source object, then it’s simpler to let them temporarily move the pivot point using the techniques covered in the pivot section. This is basically what Unity and Unreal do. Blender also supports this using the

bkey.- More dynamic options are possible (like using the closest part of the geometry dynamically to pick a point of the source) and both Blender and Roblox do this (which is funny because Blender does it to be advanced and Roblox does it to be intuitive, two different philosophies converging to the same solution1).

- Target object: How do we decide where to snap on the target object? The user is dragging the source over the target which gives us information about the user’s intent - we know where their mouse is hovering. This gives us an intersection point on the target.

- We could snap to the intersection point which is known as surface snapping, since it allows snapping to any point on the target’s surface. This feels very natural (even satisfying) as the source object glides over the target. Surface snapping isn’t good for precision though since it’s hard to hit the exact point on the target object.

- The precision problem can be solved by using vertex snapping. Instead of snapping to any point on the surface, we can snap to the closest vertex of the target object. So if the user wants to place something at the corner of the target object, they just have to roughly get close to it.

- Some applications will let you snap to edges…but I don’t really understand it. It feels like the worst of both worlds (loss of precision and loss of freedom)

Instead of doing a drag and drop, could you do geometry snapping while using the “gizmo” to move the object? One problem this creates is that the “target” object is no longer explicit. The user is no longer hovering over the target, so the application has to figure out what the target should be.

Blender and Roblox stand out here. Similar to how they have dynamic detection of a good source point, they also support dynamically detecting a compatible target. Unity and Unreal don’t really support this workflow though.

So that’s geometry snapping, how does it work on our use cases? For this discussion, let’s assume we are just doing pivot-to-vertex and pivot-to-surface snapping2.

For the chair-to-ground use case, we no longer need the ground to be placed exactly at the grid. The ground can be uneven and we would still be fine. As long as the chair has a pivot at the bottom of the chair, we can use geometry snapping to easily place the chair on the ground.

Surface snapping can even support an additional feature: rotating the source object to match the surface normal. This means that if the ground were curved or at an incline, we could place the chair so that it automatically rotates to match as seen in the video!

To snap two walls together, we can use pivot-to-vertex snapping to exactly place one wall to match the corner of another wall. This lets us easily align many objects quickly without losing precision!

Between grid snapping and geometry snapping, we get a lot of flexibility in placing objects. Grid snapping is great for “grayboxing”, where you start with an empty scene and create a rough outline of the level. Since there is nothing to snap to, the grid is all you have. Then as you start adding details, geometry snapping becomes very powerful as you can start snapping to things that exist in the space.

Other Modes

There are additional related problems that the UI also has to solve but we won’t get into in this post:

- Rotation: The same question of gizmo, pivots and snapping have to be solved for rotation.

- Scaling: Scaling also has the question of the gizmo. Users also often want to scale objects so only one side of the object “grows” (which surprisingly is just the pivot problem in disguise).

- Group of objects: if multiple objects are selected then how should the different operations behave? What pivot should be considered?

As a user of 3D applications, I hadn’t really put a lot of thought into the capabilities of the manipulator systems. I learned what each application supported and used it, sometimes happily and sometimes with frustration. Actually implementing some of these features has made me appreciate and understand the complexity a lot more.

In more detail: as you move the object, Blender will recalculate and find the point on the source that is close to any other object in the world. Roblox, on the other hand, will pick a few points on the source at the start and use that for its calculation - it does not recalculate as you move. Both pick snapping points on the source implicitly but with different amounts of user control. ↩︎

Call me biased, I have spent the past couple of weeks implementing those snapping modes at work. ↩︎