Growing up in Hyderabad, in the southern region of India, I assumed the language I spoke was Hindi. I watched Bollywood movies and TV shows. I didn’t speak any of the regional languages (like Telugu). And, you know, I was in India. So surely the language I spoke must be Hindi.

When I moved to the US and interacted with Indian people not from Hyderabad, I came to understand that I spoke Hyderabadi Hindi. It’s close to Hindi but apparently not proper Hindi. I learned that you can’t say “nakko” for negation. You should say “nahi” or “mat”. You can’t use the “-ich” suffix for emphasis. You should use the separate word “hi”. You can’t say “apan” to mean we. You should instead say “hum”. My friends found it hilarious so, like any teenager standing out, I assimilated and switched to using standard Hindi unless I was specifically trying to make them laugh.

I wasn’t alone in this realization of comedic power though. Mehmood, a comedian/actor who worked on hundreds of Bollywood movies from the 1950s to 1990s, was known for using Hyderabadi Hindi. He often used Hyderabadi Hindi when portraying characters that were unintelligent or uneducated.

Another example is the set of movies made in Hyderabad, targeting the Hyderabadi audience, where characters use a stronger Hyderabadi Hindi register when they want to be seen as sillier or ridiculous. So even native Hyderabadis seem to be aware of the lower prestige associated with Hyderabadi Hindi.

But Hyderabadi Hindi wasn’t always perceived this way. It wasn’t even called that. Historically, the language was called Dakhni.

Dakhni History

The region around Hyderabad, known as the Deccan, was controlled by various Muslim-based Sultanates (kingdoms) from the 15th to the 19th Century. Around this time, the Mughal Empire ruled over northern India and had significant cultural influence over the Sultanates in the Deccan region.

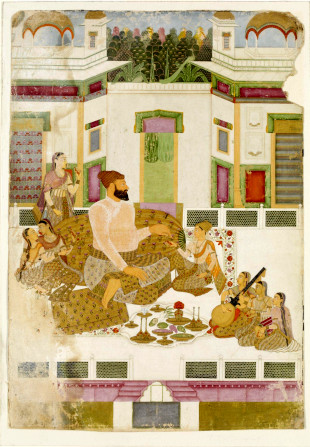

One cultural phenomenon of the Mughals was their obsession with Persian culture.1 There was a continuous effort to attract Persian elites by offering them court appointments, titles, and land ownership. Mughal art, poetry, and philosophy were heavily inspired by Persian equivalents. Even the language of the courts and the elites was Persian. And so, for a long time, this was the case in the Deccan sultanates as well.

But slowly the Deccan culture started to shift and the local language of Dakhni started being used by local poets. In the 17th century, Quli Qutb Shah, the sultan that built Charminar, wrote a collection of poetry primarily in Dakhni2. When the sultan himself is writing in the language, it’s reasonable to assume that Dakhni had become the language of the elites in the region.

I found two insightful couplets written in Dakhni from this time period.3

This one by Wajhi tells poets not to copy ideas or write about topics already covered by someone else.

Nako bol mazmun tu, hor ka;

Ke kala hai do jag mein mun chor ka.

Note the use of “nako” to mark negation which I was embarrassed about.

After the fall of the Deccan sultanates, the poets of the Deccan had to look to the Mughal empire for patronage. Many switched to writing in Persian. One poet, Hashmi, insisted on writing in Dakhni and in this couplet says that regardless of patronage, one should write in one’s native language and be proud of it.

Tuje chakri kyatu apnich bol,

Tera sher Dakhni hai, Dakhnich bol

Not only is a poet from 1686 validating my current feelings about my native language, he is doing it while using “-ich” for emphasis which was the other thing I was embarrassed about!

So Dakhni was of high prestige in the early 17th century but evolved to be of low prestige in the 21st. Since the language didn’t change itself but its prestige did, I think this shows that prestige is not about any properties of the language itself. It is the social context of the users of the language.

In modern India, the stereotype goes, if you aren’t able to speak standard Hindi or a Hindi+English combo then you must be uneducated or of a lower socioeconomic class. India is a diverse country with hundreds of languages and dialects. So my theory is that rural areas are better able to maintain their dialects because they tend to be more homogenous than cities. Rural areas also tend to be poorer and less educated so the human tendency to generalize takes over and gives us the stereotype. This is why Bollywood movies lean so heavily on using local dialects as markers for unsophistication.

Other Example: AAVE

African American Vernacular English, AAVE, is a dialect of English spoken primarily by African Americans in the US 4. Growing up in Atlanta, I was frequently exposed to this dialect and I assumed that I was hearing “broken” English. I saw it as a marker of unsophistication, just as Hindi speakers had seen in my Dakhni.

It turns out that this is a pretty common view: many people see AAVE as broken English, as a language that doesn’t follow grammatical rules. And that assumption is equally wrong in the case of AAVE. AAVE is internally consistent with its own grammatical rules. It only seems wrong because we choose to judge it by the rules of American English.

Like any other language, AAVE makes some things easier for the speaker and some things easier for the listener. AAVE has more tenses than American English which allow the listener to get more context but it requires more work from the speaker who has to correctly use those tenses. On the other hand, speakers don’t have to mark verbs for singular/plural (“She write poetry” vs. “She writes poetry” - example from Wikipedia) which makes this easier for the speaker but gives less context to the listener. All languages make these trade-offs differently but there is no inherent superiority in one approach over the other 5.

Yet there is a social penalty for using AAVE. And again, the social view has nothing to do with the language itself. Instead, it is related to the social context of the users of the language. With a long history of discrimination against African Americans, this is another thing that is assumed to be broken or wrong because it is African American.

Conclusions

In the case of both Dakhni and AAVE, the language is judged by the rules of a different language and is deemed wrong or broken. The argument goes that the language is low-prestige because it is broken but in reality, the language is being judged by the rules of a different language because it is low-prestige. While a language may seem broken, the language will have a set of strict self-consistent rules and will seem a lot more structured by those rules.

Source: The Courts of the Deccan Sultanates by Emma J Flatt [link] ↩︎

Source: Languages and Literary Cultures in Hyderabad, Chapter: “The Unique Literary Traditions of Dakhni” by Shaheen and Shahid [link] ↩︎

Initially found one couplet from Wikipedia which helped me find the book chapter mentioned above: “The Unique Literary Traditions of Dakhni” by Shaheen and Shahid. ↩︎

Of course, not all African Americans speak AAVE, and the ones that do might also be speaking a local variant. LanguageJones has a “Is it spoken the same everywhere?” section on the topic. ↩︎

I am simplifying a wildly controversial and nuanced topic. Comparing complexities of language is hotly debated amongst linguistics because even defining complexity is difficult. Here is one meta-study that finds mild support for the trade-off hypothesis and stronger support for equal complexity of languages. Either way though, the argument is can languages really be exactly complex or have slightly different complexities. I don’t think any linguist argues that some languages are holistically worse than others. ↩︎